Can Academic Health Systems be Learning Health Systems? 8 Expert Takeaways

Featuring Jodi Segal

Learning health systems can make the experience of health care more patient-centered while also advancing research and solving the problems faced by healthcare delivery leaders. They do this by bringing the tools and rigors of research to the delivery space and incorporating patient insights into the process. In theory, that should make academic health systems uniquely positioned to incorporate learning into operations, but in practice, it’s often a different story.

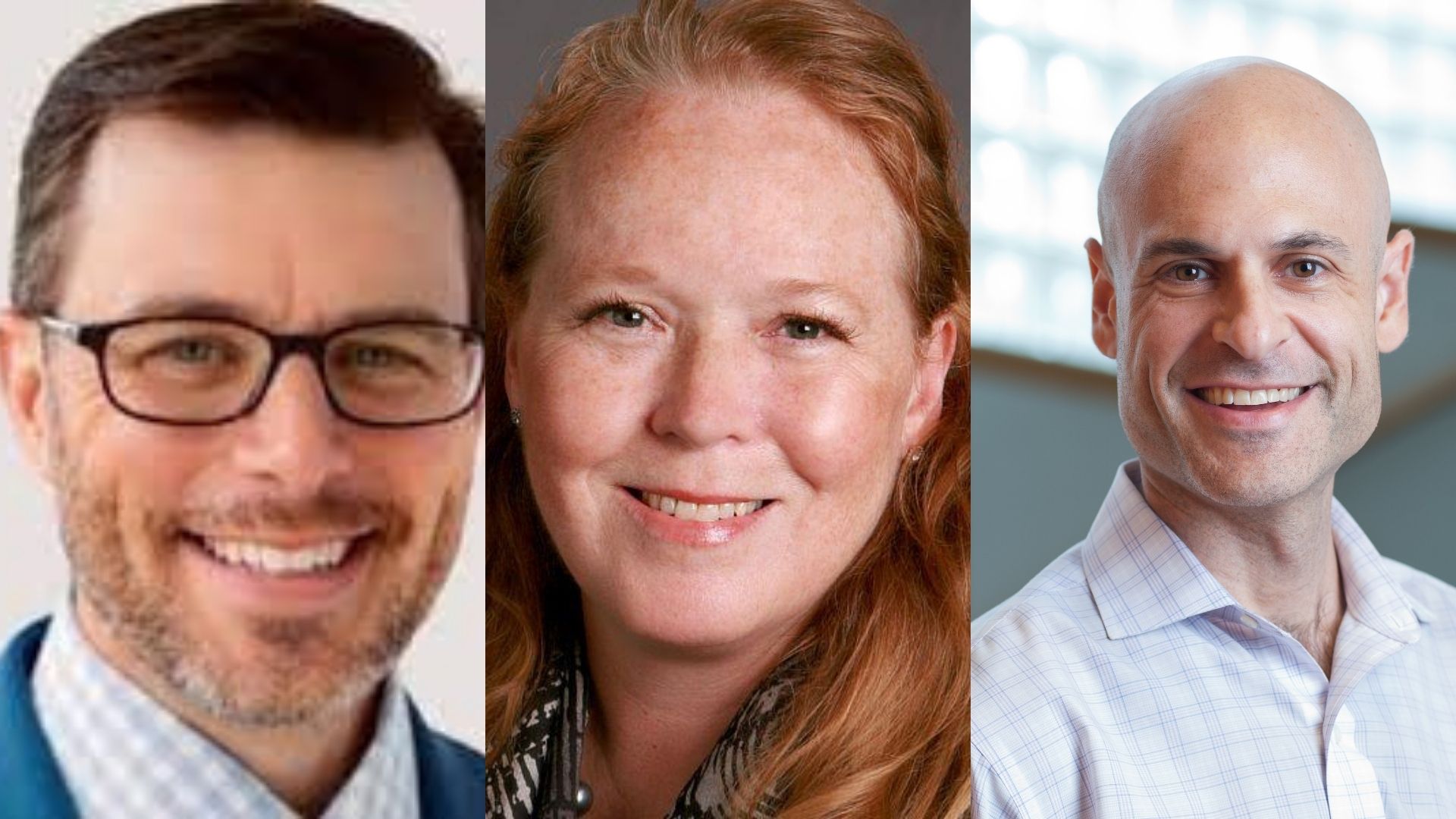

To discuss the barriers that prevent academic health systems from learning more effectively and possible solutions to these challenges, the Hopkins Business of Health Initiative convened a panel of experts to share their perspectives. The panelists included Chris DeRienzo, MD, Senior Vice President and chief physician executive of the American Hospital Association; Lucy Savitz, PhD, professor of health policy and management at University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health; Scott D. Halpern, MD, PhD, John M. Eisenberg Professor of Medicine, Epidemiology, and Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Academic health systems and academic medical centers have the resources and expertise to be effective learning health systems, but there may be misaligned incentives that lessen the impact of clinicians, researchers and operations teams working in these settings,” said Jodi Segal, MD, MPH, professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Medicine and the panel’s moderator. “I like to think that by aligning goals across research, teaching and clinical operations, Academic Medical Centers can more effectively integrate research into practice and influence their health systems.”

Here are 8 takeaways from our experts on how academic health systems may better realize their potential for learning.

- Pursue the “virtuous cycle.” Savitz refers the audience to the concept first introduced in “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” which moves health systems from performance to data, data to knowledge, and then knowledge back to performance. To improve on the model a step further, she proposes that the cycle should also include learning from peer-reviewed literature, which can be shared across health systems.

- Develop the business case and explore partnerships. For example, life science companies and electronic health record vendors share some meaningful incentives in supporting learning health system initiatives. “If we figure out redesigns of the electronic health records that make care delivery better, and if the settings in which the work is conducted could be scalable across systems, then that should have an ROI for these companies, who might be convinced to support this kind of scholarship,” said Halpern.

- Empower clinicians to inform process evolution. “If I were to boil down the notion of being a learning health system into its most basic construct, it is about how to drive continuous improvement,” said DeRienzo. To foster a culture of learning, health centers must invest in the tools and infrastructure required for a continuous feedback system, teach people how to use the tools, and most importantly, recognize and celebrate the wins when they happen.

- Focus on maturing in four key directions. Savitz explained the maturity model for learning health systems as a measuring tool defined by the following categories: leadership and governance, socio-technical environment, improvement execution, and culture and values. These areas can be used to benchmark progress and assess shortcomings and opportunities for growth.

- Establish common data standards. In order to enable collaboration and benchmarking across learning health systems, data must be accessible and transmutable. “To the extent that we can access and organize data efficiently, we are going to learn in direct proportion to that,” said Halpern. “It requires data wranglers who are skilled and who have authority to cull those data and manipulate them into analyzable sets, and it requires an overall governance structure that ensures that appropriate privacy considerations are respected and promoted without unnecessarily limiting access to data.”

- Imagine possibilities outside of health care. Like the rest of the industry, learning health systems are challenged to go beyond clinical settings to examine the drivers and disparities in community well-being. “As we think more broadly about the extension of health care into more of what we define as health, there are going to be opportunities to learn beyond the walls of health systems to the rest of the community,” said DeRienzo. “And there are plenty of opportunities to think creatively moving forward.”

- Engage patients in research. All three panelists identified the incorporation of patient’s lived experiences as a key component of the data produced by learning health systems. “Basically what we're trying to do is to really take knowledge that's generated from the data that we collect as an artifact of the care that we're delivering health care and then actively engaging patients and families across the entire process,” said Savitz. “So now we have a real patient perspective in our work, even from the design of the study to articulating the questions that are going to be answered and all the way through the dissemination of the research.”

- Embrace non-conformity. “I always say the same thing about learning health systems: you've seen one, then you've seen one. They're all very, very different, and they start in very different kinds of ways. Some start from the grassroots at a small scale, and others are a top-down decision that's made by leadership in an organization,” said Savitz. “I think our tendency to try and create a box, to define things and set a framework around them, sometimes eludes the fact that there is this sort of amorphic kind of possibility that exists.”